Some labor market considerations from the ACA decision

It’s been two weeks since we have all learned of the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Since the announcement, Republicans have been roiling over the ruling while ramping up efforts to repeal the act in its entirety (the House just held their 31st vote of this Congress to repeal the act). Democrats, meanwhile, have been largely ready to move on from the discussion and on to “greater” issues in the national policy spectrum. What has been largely missing from any of the national media attention around the ACA has been the effect the Supreme Court decision will have on labor. While the individual mandate was found constitutional under Congressional tax powers, the Supreme Court also determined that the states cannot be penalized for failing to expand their Medicaid programs to cover everyone up to 133% of the poverty level as envisioned under the law. Both rulings will have significant effects on many different groups of workers. The first of which is how employers will respond to the necessity of insurance coverage or facing a tax. The second and equally if not more troubling effect is the implication for those falling in what I am terming the insurance gap.

The original purpose of the act was to insure all Americans. This was due to the large number of uninsured in the U.S. (nearly 50 million in 2010 according to the Census Bureau) creating a large amount of non-coverage charges and in effect passing those costs on to insured consumers. Aside from collective cost issues, insurance for all is important for labor concerns as well. Gallup has been tracking the number of uninsured in the U.S. through their well-being index and found that since 2008, the percentage of adults 18 and older without health insurance has increased from 14.8% to 17.1% in 2011. Much of that increase can be attributed to the disastrous jobs situation in the U.S. since 2007, but we cannot be assured that the rate will decrease as jobs come back. That is evident in a more recent Gallup poll which has been tracking employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) by age group from 2008 to mid-2012. Even though jobs have been added to the economy every month since late 2010 (see BLS report here), the percentage of the population that has ESI coverage has continued to drop substantially. From 2008 to 2010, the best employed age group (26-64 year olds) saw a 3.5% decrease in employer coverage, and it dropped another 2.2% under increasing employment conditions. While it is very likely the continued decrease in employer provided insurance is due to cost cutting by employers to cope with the economy and the lack of bargaining power that labor unions have to keep the benefits, there are no widespread surveys to truly understand what is happening.

The ACA is meant to remedy the loss of ESI to some extent in 2014 by implementing taxes on employers not providing insurance and tax incentives for individuals and families making under 400% of the poverty level. By taxing ($167/month per full time employee in excess of 30 with increasing penalties over time) employers with the equivalent of 50 or more full-time employees if any of their employees are not covered by an employer-sponsored health plan, the ACA is expecting employers to take a high road approach and maintain or add health insurance plans for their employees. The fault in that expectation is that those taxes rest far below the cost of actually insuring their employees and is likely to lead many employers, especially those with fewer than 100 employees to opt out of paying for insurance if they are not already doing so. Companies that are currently offering insurance to their employees may reevaluate whether or not to continue insurance coverage for their employees. This is due to the tax incentives that are available to workers earning between 133% and 400% of the poverty level. Several options are available to employers to comply with the law, and one such option is to give their employees a free choice voucher in order to purchase their own insurance in an insurance exchange. A McKinsey Quarterly report from from a survey they conducted last year found that when employers give their employees a voucher to purchase their own plans, 70% of employees chose a less expensive plan than the employer was going to offer, thus saving the company money. However, that may not provide the kind of coverage an employee needs or desires.

For those left to purchase insurance on their own, the tax credits available to individuals and families earning under 400% of the poverty level could affect their willingness to pressure their employer for another option. Under the incentive rules, those at 400% of the poverty line will see their health care expenses capped at 9.5% of their income. That means a family earning $80,000 a year could be responsible for up to $7600/year in health costs or $633/month and anything above that would be covered by tax incentives. The incentives may be insignificant enough that a backlash could ensue. With the amount of debt the American public has accrued, asking people to contribute nearly 10% of their income to health insurance may be a burden they will be unable to cover. Luckily, there are hardship exemptions, but how lenient the IRS will be with those is a large grey area at this point. The concern for those at the tail end of the tax incentive income bracket is likely to be blunted substantially due to the fact that higher incomes usually mean employers act more competitively with those employees and will be more likely to offer health benefits to do so. As such, those left without ESI at the tail end of the bracket will likely have fewer collective voices to bring attention to the cost burden problem. The larger concern out of this is that without the Medicaid expansion in all states, there will be millions of low-income workers that will be severely harmed by the ACA.

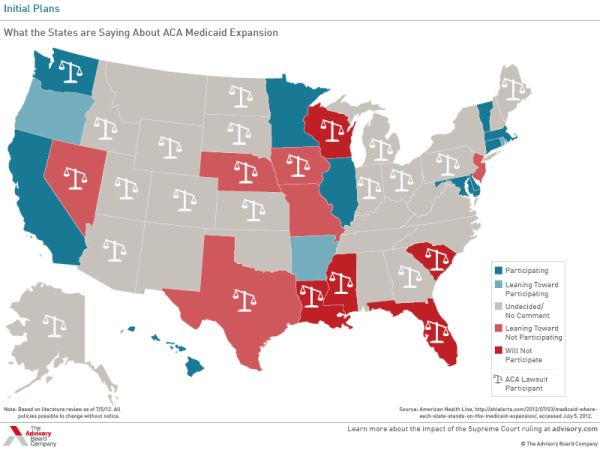

At the lower end of the economic ladder poor and low-income workers were to see large benefits come to them from the ACA. The Supreme Court ruling put some of that in jeopardy. Without being able to penalize states that do not agree to expand Medicaid rolls to include everyone up to 133% of the poverty level, millions of workers are likely to see large health care bills in their future. Seven Republican governors have pledged to not expand Medicaid and many more can be expected to opt out considering their involvement in the lawsuit against the Federal government over the ACA (see map below or a larger version here). Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius sent a letter to the states on July 11 saying that should they opt out of the Medicaid expansion, their low-income population will be eligible for hardship waivers. That’s a relief for low-income workers, but it also means they will fall into the insurance gap by being the only substantial group, except for undocumented immigrants, that will remain uninsured. At the very least, it appears that states can still be penalized with the loss of all Medicaid funding if they restrict access to Medicaid any further, providing they do not file for a exemption due to budgetary constraints. The insurance problem for low-income workers is only further complicated by looking at where low-income workers are employed and how that impacts their insurance status.

Low-income workers are rarely provided ESI for the primary reason that a large majority of them are part-time employees. A 2009 report from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey showed that between 1996-97 and 2005-06 even full-time low-income workers have been left out of ESI coverage (See Chart 1 recreated from the report). With the growing number of low-income workers and part-time employment, the situation becomes more dire. Nearly half the 7.5 million worker growth of low-income workers in the U.S. was in part-time employment (3.6 million) while most the other half was growth in unemployment (See Chart 2 recreated from the MEPS report).

Chart 1: Insurance Status by Family Income for Non-Elderly, Full-time/full-year workers excluding self-employed, 2005-06#

Chart 2: Population of Low-income Workers by Employment Status, in Millions: 1996-97 to 2005-061

If it is expected that low-income workers are to be helped out by the employer requirements of the law, that expectation is likely to fall short. Part-time employees are not covered under the employer mandate portion of the ACA, but large employers will be penalized for employing a part-time employee that has claimed a premium credit for insurance from a state insurance exchange. This could make large employers more selective about who they hire and may lead employers to re-evaluate the costs and benefits of having part-time vs. full-time employees. Should employers find the costs pan out to have more full-time employees, that will be good for a select few workers, but many others will go unemployed as a result. Business size will also factor into the situation considerably. According to the MEPS report, in 2005-06 nearly 70% of full-time non-elderly low-income workers were employed in establishments with fewer than 100 employees. Over 45% of those were working in establishments with fewer than 25 employees. Since the ACA only mandates that employers with 50 or more employees participate, the growth in ESI coverage is likely to be minimal for low-income workers. While tax credits will be available to small-businesses (those with fewer than 25 employees) to provide or maintain health benefits for their employees, it is not likely that the small businesses in which a majority of low-income workers are employed will be providing any additional health coverage than they already are. Even then, the tax credits only last for 2 years.

What will be left is a fairly significant portion of the population that will still be uninsured. These will be households that already are struggling from high costs of housing and transportation in most metropolitan areas. Low-income workers that fall into the insurance gap between qualifying for Medicaid and without ESI will face a problematic labor market status. Their lower income competition will have health care provided to them so that they can stay healthier and thus more productive. Since they provide a lower labor cost to the employer, their usefulness to the employer will put them at a labor market advantage over just slightly higher income workers. Meanwhile, by not having insurance, the low-income workers that fall into the gap can see their health falter leaving them at a disadvantage over other workers of similar income that were able to get insurance through their employer. Not only can their health put them at a disadvantage, any medical emergencies could easily put them in severe debt and limit their employment opportunities as more employers are checking credit scores for potential employees.

Ultimately, many millions of workers will be aided by the ACA as it is implemented over the next few years even with problems to fix for those in the insurance gap and the large amount of pure speculation in how employers will decide to act. Employers that already offer insurance are likely to continue offering insurance in the future, but if they employ a large proportion of low-income workers, they may find it better to offer vouchers instead. Should this law actually transition employers into hiring more full-time employees, we could see a climb in unemployment. One thing that is not likely is that the tax penalties or insurance premium costs will substantially dent hiring, especially among employers at or near the 50 employee mark as many conservatives have claimed. The reason for this is that the tax penalties will not be substantial enough to offset the profit growth obtained by expanding employment and, in effect, output. Also, Factcheck.org checked the GOP claims that the law will kill jobs, and their analysis found only the Congressional Budget Office and The Lewin Group had provided non-partisan analyses on the job effects of the law as of January 2011. Both said the job losses would be small with most the losses made up by gains in the healthcare industry. The Lewin Group expects some employers to turn to more part-time employment, but I still suspect that employers would be more likely to turn to vouchers for all employees or more full-time employment over the risk of employing a part-time worker that could trigger tax penalties far in excess of the cost of the part-time worker. For employers that choose to accept the tax penalties, it would be possible to employ part-time employees with no risk. In the end, the complications and inefficiencies brought about by this law and the subsequent Supreme Court ruling will make many wish we had a single-payer system instead. But, since this is what we were given, it is the system we will have to work with for the foreseeable future.